Tracing the Threads:

A Look at Keenan Reimer-Watts's Variations for the 21st Century

Introduction

Composed in 2016 and modelled on J. S. Bach's Goldberg Variations, Keenan Reimer-Watts's Variations for the 21st Century consists of an Aria and thirty variations. Like the Goldbergs, Reimer-Watts's Variations traverse a wide range of moods and affects, and together constitute a beautifully crafted tapestry of vivid colours and sensual textures.

In an interview with him, Reimer-Watts made several notable comments about the composing of Variations for the 21st Century. First, he stated that the work is a set of variations on the bass line of the initial movement, the Aria. Second, he noted that the Aria itself was a variation of a pre-existing work, the fourth movement of his earlier Wandering Pieces. Third, he said that after composing the Aria, he sketched out the first few measures of each variation before composing any of the variations in full. Finally, Reimer-Watts talked about how structural elements of the Aria were reused within the movement, and about how the existence of these internal references necessitated the use of variation techniques within each movement. This analysis therefore, was begun with the hypothesis that two fundamentally different techniques of variation were employed in its composition, one acting between movements and the other within them.

The first of these variational procedures, acting between movements, will be referred to as conventional variation. In this type of variation, a range of familiar procedures such as transposition, addition of embellishing tones, melodic inversion, rotation of voices, change of mode, and so on are employed to vary a model passage without changing its deeper character. The second type of variation will be referred to as innovative variation. In innovative variation, while some material is preserved from a model passage, a change in character is effected – a new texture is created, a new approach is adopted, or new material is composed around what remains of the model.

Looking at the material of the Aria, and comparing it to model passages in Wandering Pieces: IV, examples of both conventional and innovative variation are readily found. In examining a later variation in the set, however, it becomes apparent that Reimer-Watts's approach to variation form is not so straightforward.

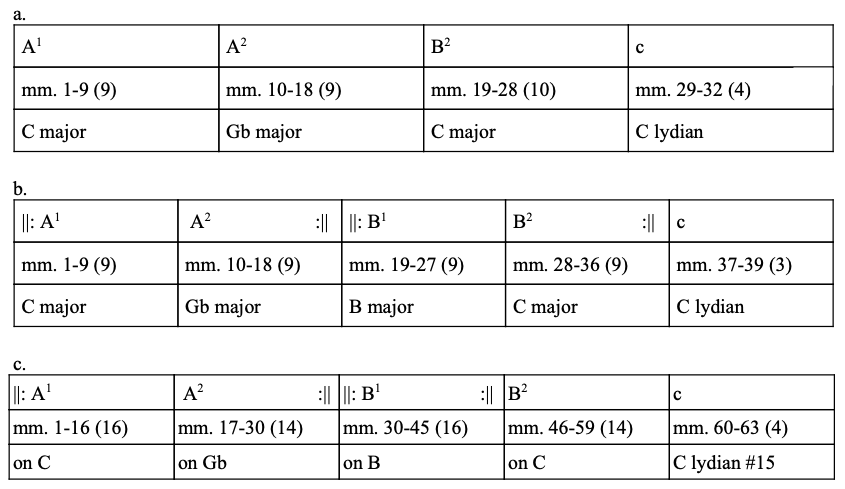

The Form and Character of Wandering Pieces: IV

To begin teasing apart the variational techniques used in crafting the Aria of Variations for the 21st Century, we must begin by looking at the fourth movement of Wandering Pieces (Wandering Pieces: IV). The piece consists of three nine-measure phrases followed by a four-measure coda, creating an A B A’ C form - these four sections will be referred to as A1, A2, B and c due to their correspondence to sections of the Aria. Each phrase begins with four measures clearly suggesting a tonal centre after which the phrase moves into a stretch of non-functional harmony with the introduction of numerous chromatic pitches. Phrase A1 begins in the key of C Major, A2 begins in Gb Major, and B2 represents a return to C Major; the coda is diatonic to C lydian (See Fig. 1a).

It is worth examining how the harmonies of the piece's initial measures outline the key of C major. On the downbeat of each measure, a chord in a spread voicing is sounded, while on the measure's second beat a closed-voiced triad, chosen so as to not share any pitches with the preceding chord, is sounded in the piano's middle register. The downbeat triads seem at first to behave functionally, constituting I, vi, V and ii6 triads in the key of C major, while the embellishing triads add colour to the predominating chords while clearly not acting functionally. In the accompanying score, the main triads have been labelled with chord symbols, while the ornamenting triads have been labelled with circled chord symbols (Appendix 1). This technique of voicing embellished triads can also be observed in the piece's coda.

Notably, Wandering Pieces: IV is monothematic, in that the A2 and B2 phrases each contain material drawn from piece's opening measures. The first three measures of A2 are a transposition of the opening of A1, moved upwards by the interval of a diminished fifth, while the first seven measures of B2 are derived from A1 by transposing both hands outward by one octave. These transpositions and changes of register are simple examples of processes of conventional variation, creating some contrast within the movement, while leaving the piece's character intact.

From Wandering Pieces: IV to Aria

The form of the Aria is somewhat more complicated than that of Wandering Pieces: IV. It contains four nine-measure phrases rather than three, with an added phrase in B Major, B1, inserted between phrases A2 and B2, causing the key areas of C Major, Gb Major, B Major and C Major to be visited during the course of the movement. These phrases are then grouped in pairs that are bracketed within repeat signs, leading to a form that can be described using the labels ||: A1 A2 :||: B1 B2 :|| c (See Fig. 1b.).

Before seeking out examples of the innovative variations that link the Aria to its model, it is worth noting that some instances of conventional variation connect the two works. A series of six-note chords is located at the end of the B2 phrase of both pieces: displaced by an ascending octave in the Aria and notated in eighth notes rather than quarter notes, these chords are otherwise copied verbatim from the earlier composition. Similarly, the closing section of the Aria is derived from the closing section of Wandering Pieces: IV through the small conventional variations of a change in register and tweaks to the voicing of chords. Since none of these manipulations change the character of the passages, they constitute examples of conventional variation.

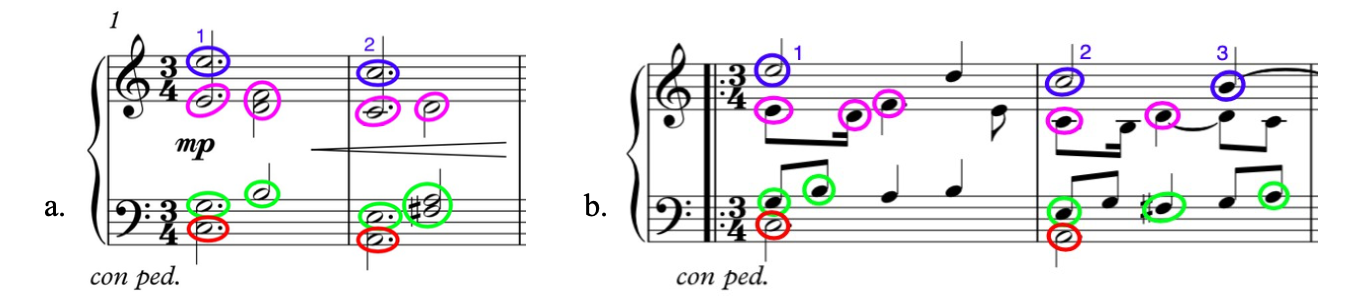

The first example of innovative variation presents itself when the opening measures of both pieces are compared. Wandering Pieces: IV is chordal in texture, and the Aria is written in a four-voiced contrapuntal style, yet the initial sonority of both pieces is identical – a C major triad in spread voicing. The second note of the Aria's tenor voice and the second and third notes of the alto voice constitute a B diminished triad – the same embellishing triad found in the first measure of Wandering Pieces: IV. By examining the following measures, Reimer-Watts's process becomes clear: the lowest pitch of the downbeat chord in Wandering Pieces: IV becomes the bass voice, while the higher pitches in each measure form the framework of the soprano voice, to which embellishing tones are added. The tenor and alto voices “spell out” the inner notes of the voicings from Wandering Pieces: IV, with the addition of more embellishing tones. While the upper three voices of the Aria sometimes dance around the notes of the model rather than landing on them, the vast majority of the notes of Wandering Pieces: IV's chords can be found distributed among the four voices of the Aria (See Fig. 2).

This constitutes an example of innovative variation because, even though it displays some properties of conventional variation such as the addition of embellishing tones, it results in a profound change in character between the two passages. While Wandering Pieces: IV is chordal in nature, the contrapuntally-textured Aria is fundamentally melodic in nature.

Conventional Variation in Aria

The Aria’s A2 phrase displays a familiar conventional variation, beginning with three measures borrowed from the movement’s A1 phrase transposed upwards a diminished fifth as in Wandering Pieces: IV. The B1 phrase of the Aria features another transposition of the material from A1 to the key of B major, with the RH moving upwards a major seventh and the LH moving down a minor ninth, but a closer inspection of the passage reveals another subtle but clever conventional variational technique. Examining the two inner voices, it is apparent that while each voice presents the expected pitches, the tenor does so using the rhythms of the alto voice and vice versa. This process occurs only in the phrase's first two measures, and is far from enough to give the passage a new character, but it nonetheless lends the passage a slightly different flavour.

A glance at the B2 phrase reveals a few more conventional variations. Compared to the A1 phrase, the bass voice has been transposed downwards an octave while the tenor voice remains at its original pitch. This necessitates that rhythmic variations be applied to both voices, allowing the LH to jump between the two parts. Meanwhile in the RH, the soprano voice has remained at pitch while the original alto voice has been transposed upwards two octaves, effecting a contrapuntal inversion of the two voices. These processes of transposition, rhythmic variation and rotation of voices maintain the character of the movement's opening while adding some variety to the movement's recapitulation.

From Aria to Variation 29

Let us now compare the Aria of Variations for the 21st Century to its twenty-ninth variation. As it is the penultimate variation in the set, we should not be surprised that some unconventional tactics are adopted to keep things sounding fresh. The form of this variation already departs somewhat from the Aria's model: whereas in the Aria, the B1 and B2 phrases are together enclosed between repeat signs, in this variation, the B1 phrase alone is repeated while the B2 phrase is played only once (See Fig. 1c). Moreover, while a single texture – contrapuntal in four voices – predominated in the Aria, three distinct textures can be found in the variation's four phrases. Within the A1 and B1 phrases, there is an alternation between passages of thick chordal wedges, and passages of running arpeggios of triplet sixteenth-notes. The A2 and B2 phrases, however, feature a two-against-three polyrhythm between eighth-notes in the right hand and triplet eighth-notes in the left. While all of the structural bass notes from the Aria are preserved, the existence of such textural contrast suggests at the very least that three separate instances of innovative variation have taken place in the composition of this variation.

The first texture consists of a series of chordal wedges, each formed over the course of two measures. Looking at mm. 1-2, the first chord consists of two notes separated by the interval of a second, the lower note of the dyad being a C that corresponds to the first bass note in the Aria. In the second chord, the lower voice falls by a step. The lowest pitch continues to descend by step in the following two chords of three and four notes. In m. 2, the RH notes of m. 1 are repeated in the LH an octave lower while the RH plays a succession of three- and four-note chords. The same process of chordal expansion occurs in mm. 3-4, with the lowest note of the initial dyad being an A, the second bass note of the Aria.

The structural pitches of the Aria's bass line form the literal bass line in the second and third textures. In the passage of triplet sixteenth-notes beginning at m. 5, the lowest, initial pitch of the first arpeggio corresponds to the Aria's third bass note, while at the beginning of the B1 phrase, the lowest pitch of the LH's arpeggios in triplet eighth-notes again corresponds to the beginning of the Aria's B1 phrase as it supports the RH's melody in eighth-notes.

Variational Techniques within Variation 29

The variational techniques employed in Variation 29 range from simple to complex, and the simplest of these can be observed by contrasting the initial appearance of the movement's second texture in m. 5 to the texture's return in m. 35. In an example of conventional variation, the technique of inversion of contour is in evidence as earlier ascending arpeggios are answered with descending arpeggios. Looking at the beginnings of the A1 and B1 phrases, we can see that a similar contour inversion is employed: the lowest pitch of the initial dyad is a structural pitch in both instances, but whereas the lower pitch stepped down in m. 1, the upper voice steps upwards in m. 31a. A second layer of conventional variation is applied when the RH pitches m. 31a are repeated in the LH in m. 32 not as chords but as ascending arpeggios.

A comparison between the variation's A2 and B2 phrases is also instructive. The texture in both passages is one of a melody in eighth-notes in the right hand supported by quickly changing arpeggios in the left, but while the melody is played in single notes at m. 17, it is played in octaves in m. 46. This textural thickening is further increased at m. 54, where the RH octaves are replaced with four-note chords and the LH arpeggios using two notes at a time.

The truly remarkable comparison, however, is between the beginning of the variation's A1 phrase and its A2 phrase. In the A1 phrase, the interval between the two pitches of the initial dyad is a major second; in the second chord, the distance between the two outer pitches is a minor third. Continuing to comparing outer pitches, we find a perfect fourth and then a major sixth. In looking at the melody in the A2 phrase, we find the same succession of intervals – an ascending major second, an ascending minor third, a perfect fourth, a major sixth. What has happened is that the outer pitches of the initial chordal wedge have been transformed into a compound melody.

This transformation, from chordal wedges whose quality is more textural than tonal into a compound melody supported by a fast-changing arpeggiated accompaniment, is much more drastic than any of the other within-movement variation techniques seen so far. The texture is dramatically different, and the character of the B1 phrase contrasts markedly with that of A1 – this is an innovative variation in which a passage is based on a model found within the same movement. At the climax of Variations for the 21st Century, Reimer-Watts presents a tour de force of variational technique.

Tracing the Threads

It is clear, then, that Variations for the 21st Century is woven thick with references to earlier passages in the same work, and it is worth examining the composition's warp and woof by considering one passage and tracing all its referents. The second half of the B2 phrase of Variation 29, beginning at m. 54, is a conventional variation of the phrase's beginning, with a thickening of the texture achieved by replacing RH octaves with full chords. The B2 phrase itself is a conventional variation of the beginning of the A2 phrase of the same movement, transposed by a tritone and with the RH part doubled at the upper octave. The A2 phrase is a variation of the A1 phrase, with the contour of the movement's opening chords spelled out in the right hand's compound melody - an innovative variation. Meanwhile, the B2 phrase of Variation 29 is also an innovative variation of the B2 phrase of the Aria, the two passages sharing a bass line. The A1 phrase of Variation 29 is modelled on the A1 phrase of the Aria, preserving the bass line of the earlier movement but discarding the Aria's other pitch and rhythmic content. And the A1 phrase of the Aria is based in turn on the opening measures of Wandering Pieces: IV in an innovative variation that preserves the earlier work's bass and soprano framework and realizes the piece's inner harmonies as rhythmically varied alto and tenor voices.

But this is not all: in the front-matter of Variations for the 21st Century, Reimer-Watts states that “The performer is free to improvise on the notes, if they so choose.” As such, each rendition of m. 54 of the work's 29th variation constitutes a variation (improvisation) on a variation (the second half of the B2 phrase) of a variation (the first half of the phrase) of a variation (the B1 phrase) of a variation (the A1 phrase) of a variation (the Aria's A1 phrase) of the opening measures of the fourth movement of Wandering Pieces. A thick weave indeed!

Conclusion

In conclusion, the monothematic nature of the Aria of Variations for the 21st Century posed unique compositional challenges for Reimer-Watts, and these challenges inspired remarkable creativity in the treatment of recurring material within the piece. With conventional and innovative variations occurring within and between movements, it is clear that the work is tied together by a tight web of internal and external references.

Appendices

- Appendix 1: Annotated Score of Wandering Pieces: IV

- Appendix 2: Annotated Score of Variations for the 21st Century: Aria

- Appendix 3: Annotated Score of Variations for the 21st Century: Variation 29

- The full score of Variations for the 21st Century, along with recordings of individual movements, is available through the IMSLP.

- The full score of Wandering Pieces, along with recordings of individual movements, is available through the IMSLP.

This analysis began life as part of my application for the Master's in Music Theory program at McGill University. I'd like to thank Keenan Reimer-Watts for taking the time to talk about the piece with me, and Dr. Terry Paynter for his feedback and guidance.

Posted: Nov 21, 2020. Last updated: Aug 31, 2023.